Midwest Scrap Management – 8116 Wilson Rd, Kansas City, MO 64125

An Extraordinary Challenge at a Massive Industrial Operation.

Our work in the Blue River Valley Industrial Corridor in northeast Kansas City stretches back more than three decades and dozens of projects. One thing we’ve learned is to expect the unexpected from land that’s been put through the rigors of industrial production over and over again. The unexpected is exactly what Midwest Scrap Management came up against when they called us in to get to the bottom of a complicated foundation problem.

A Mismatch of Old and New.

Midwest Scrap Management is a premier metal processor with locations across the region. At the center of the company’s Kansas City operation is a mega shredder that chews up everything from old cars to even larger pieces of industrial scrap metal. Cranes send the scrap up a conveyor to the shredder and the evenly chopped results are separated and organized into piles around the property for recycling. Think tree mulching that’s bigger than you can imagine until you see it with your own eyes.

Conveyor loaded with scrap headed for one of the biggest shredders on the planet. Courtesy: Midwest Scrap Management

Conveyor loaded with scrap headed for one of the biggest shredders on the planet. Courtesy: Midwest Scrap Management

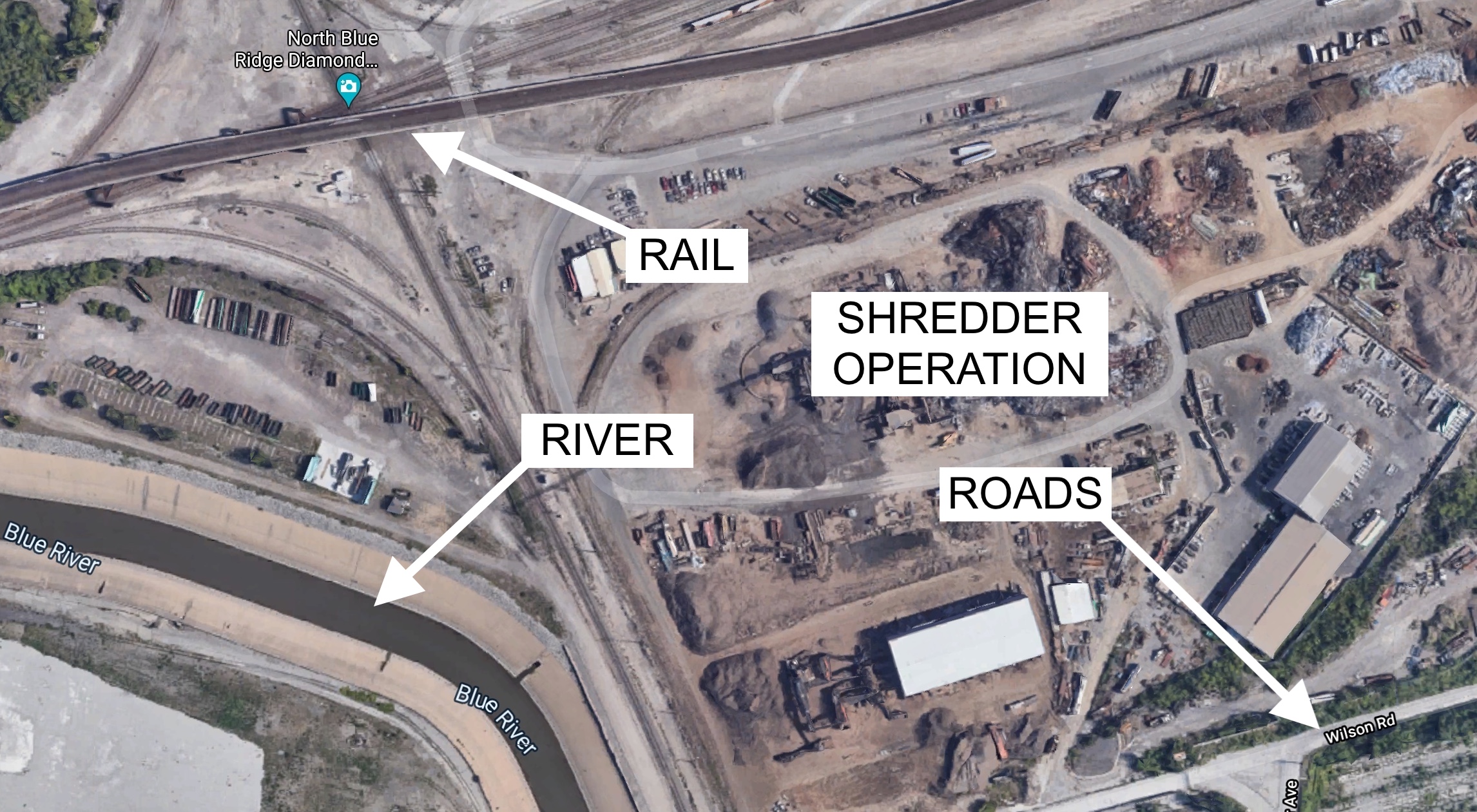

An overhead view shows the enormous scale of the shredder operation and the material piles it chews through.

An overhead view shows the enormous scale of the shredder operation and the material piles it chews through.

When Midwest Scrap Management moved into the Blue River Valley Industrial Corridor (BRVIC) several years ago, the company knew it found an ideal property for its colossal metal shredding operation. It was near train tracks, a river, and key roads — all the access you expect at a well-established industrial hub. The property also offered the benefit of deep foundations originally built to support the manufacturing of steel and steel products as far back as the early 1900s.

The Midwest Scrap Management property in a prime spot within the Blue River Valley Industrial Corridor.

The Midwest Scrap Management property in a prime spot within the Blue River Valley Industrial Corridor.

The shredder itself and the gigantic motor that powers it were each positioned on separate, existing foundations. Anyone familiar with the Corridor will tell you there’s not much reliable documentation detailing the parameters of old foundations. What we do know is many are strong, deep and originally built to last an extremely long time. Midwest Scrap Management couldn’t be sure whether their foundations were anchored all the way down to unshakable bedrock. Over time, they found out the hard way.

“It became obvious that the motor and shredder foundations were slowly sinking,” remembers AOG Engineering Director Garic Abendroth. “Workers at the facility had done all they could to make adjustments to compensate for the movement, but it just wasn’t enough.”

Midwest Scrap Management’s shredder process is in very high demand, operating non-stop with only a couple of weeks of downtime for maintenance each year. A steady stream of metal scraps continually flows from salvage yards, rail companies, construction companies, farms, the list goes on and on. That’s quite a load on the foundations. And then there’s the vibration.

“The load alone is really something, and then you add the vibration from the equipment and you’re putting extreme demands on the foundations,” says Abendroth. “A huge motor cranking at thousands of RPMs plus giant steel blades churning. I’ve seen a lot of massive industrial facilities and equipment, but this one was different. All the forces at work shake the entire property and it rarely stops.”

After a few years, the situation started raising real questions about the long-term viability of the foundations. Our engineers were called in to take a closer look and soon recognized that the foundations might have held up okay under the weight alone, but the vibration in addition to the load was just too much.

“Vibration shakes up soil particles in a way that weakens the soil,” explains Abendroth. “In fact, vibration is often used purposely to help drive objects into soil. Even something as small as a vibrating stop sign post can be inserted in the ground much easier than just pushing or hammering. The shredder equipment was creating a similar effect on its foundations and surrounding soil.”

“You’re already working in the sand and silt of the Blue River valley,” adds AOG President Allan Bush. “All that vibration is consolidating and densifying all of those particles over time. Without foundations going all the way down to bedrock, sinking is going to happen and keep happening. In this case, the vibrations are so powerful that they’re probably going down over half the depth of the Blue River Valley channel.”

Wide cracks from relentless vibrations opened up in walls of surrounding buildings on the property.

Wide cracks from relentless vibrations opened up in walls of surrounding buildings on the property.

The search for a solution focused first on whether anything could be done to stabilize the existing foundations. Over months, we huddled with deep foundation specialists and others to determine the potential and the conclusions were discouraging. Saving the existing foundations would be too expensive and we couldn’t guarantee it would even work. Abendroth says there were just too many unknowns.

“If we try to dig down along these foundations to underpin them, we don’t know what we’re going to find. Even if you deployed sonar or similar technologies, the risk of buried steel interfering with the readings was high. That’s a very expensive endeavor for what would yield limited results. Plus, the chance of ultimately finding conditions that we can’t overcome is real and then you’ve wasted all this money just to confirm a problem you already know you have.”

As we investigated, we also worked closely with Midwest Scrap Management to understand business priorities that would be critical in shaping the right solution. Taking the shredder operation offline for an extended period of time for foundation work wasn’t an option because uninterrupted production was paramount. And dumping potentially millions of dollars into repairs that may not hold up in the long run wasn’t an option either.

“This was a complicated problem and we had to stay in close communication with the owner as we explored what was possible,” says Bush. “I think that’s something that sets us apart at AOG. We really believe robust communication and collaboration are essential for achieving the best results on the right terms. Garic, especially, worked hard to help the owners understand what we were up against as engineers, and what they, as a company, were facing from a business standpoint.”

The Switch to a Fresh Start.

The decision was made to abandon the existing foundations and build from scratch on a different area of the property. It was a smarter investment that could deliver peace of mind lasting decades without worry. It could also be done without significantly interrupting shredding production. The final plan called for establishing a new facility on new foundations better matched to the realities of the shredder operation, and then simply switching production from the old site to the new site without missing a beat.

AOG evaluated the property and identified the right spot for the new facility. It fit the workflow of trucks and trains, and offered bedrock within reasonable reach of driven steel piles that would protect against substantial shifting or sinking.

“We dug borings to see exactly what was possible with the bedrock,” remembers Abendroth. “Deep foundations with hundreds of driven piles were just too expensive. So we took a harder look at balancing cost with performance and determined we could create far fewer piles and just strategically locate them in key spots to handle the facility’s heaviest work. A consistent bedrock level across the build site we chose was a bonus.”

But the news wasn’t all good at the new site. Not surprisingly, the top layer of the subgrade was like much of the rest of the Blue River Valley Industrial Corridor — brownfield. At AOG, we’re known for making the most of available material rather than just automatically exporting it, even if it’s not ideal. However, Bush says this was an exception.

“We were dealing with a layer of very old industrial brownfield and a risk of hidden obstacles like car-size debris, legacy structures and other objects blocking the drills. Plus, we were on a timeline that involved the arrival and installation of new shredder equipment, which meant we wouldn’t have time to try to work around obstacles as they popped up. So we dug out about ten feet of ground across the site and replaced it.”

Digging out a top layer of industrial brownfield riddled with metal chunks, boards and concrete.

Digging out a top layer of industrial brownfield riddled with metal chunks, boards and concrete.

Rubble fill is the least of what you can expect from Corridor brownfield.

Rubble fill is the least of what you can expect from Corridor brownfield.

Replacing the ten-foot top layer wasn’t as easy as just scooping it out and dumping in new fill material. Abendroth says underground water making its way to the nearby Blue River poured in as the soil was removed. “Ten feet down we’re still above the water table, so all the water from higher ground is draining toward the river at that level. While the digging was underway, the water got a few feet deep.”

Test pits revealed water just a few feet below the surface making its way to the river.

Test pits revealed water just a few feet below the surface making its way to the river.

“This was complicated and the foundation work hadn’t even started yet. It was just site preparation!” adds Bush. “Stabilizing the ground while you’re also dealing with water takes experience. You have to really be ready to roll with the unexpected. But when you’ve been down this road so many times like we have, you come prepared. You get your ducks in a row with pumps and an understanding of the bigger picture before you get started. For example, you’re mindful of the river level itself and plan accordingly because if the river rises while you’re working ten feet down, you have a big problem. You can’t pump the river dry.”

“We basically had to keep bailing water until we had enough gravel pushed down to hold the water back so we could continue,” says Abendroth. “A good sense of timing during the process is a real advantage in working through these kinds of situations.”

Filling the excavated layer with gravel to build it back up to ground surface level.

Filling the excavated layer with gravel to build it back up to ground surface level.

New fill material and a strategic grading project.

New fill material and a strategic grading project.

After the subgrade was in good shape and construction began, AOG’s special inspections technicians moved in to make sure all the work strictly complied with the engineering plans. Our team played an especially critical role during construction of the driven piles. Welding specialists supervised the construction of every pile as long steel beams were carefully connected to reach all the way down to bedrock.

“You actually have to stand each piece up and drive it down, connect the next piece and so on,” says Bush. “You’re welding them vertically as they go into the ground.”

“It’s meticulous welding,” adds Blake Bennett, our Business Director and veteran special inspections expert. “Many of these welds are full penetration welds creating a continuous piece of steel. If you don’t do it exactly right the piles can fold as you’re pushing them down or fail later after they’re in use.”

AOG field techs monitored all the soil and concrete work too. And in this case, the amount of materials was several times a more typical construction project. “The massive character of this project really defined it,” says Bennett. “We’re talking walls that are feet thick, not inches. Every piece was huge. Construction took about a year.”

It’s hard to overstate the role of our AOG inspections team in a project like this. We take a lot of pride in mapping out creative engineering solutions that draw on our long experience and unique expertise, but it’s our field techs who make sure every detail, from rebar to specialized welds, materializes as planned.

“Our ability to execute and precisely nail down a custom solution hinges on the extremely high confidence we have in our field technicians,” Bennett stresses. “They have a great deal of experience as well, and the trust we all share, as a firm, allows us to do the difficult projects we’re known for. It’s not just about reports and recommendations, it’s about observing the work, validating decisions, and adjusting to changing conditions throughout construction to the very end. That’s the full equation behind complicated solutions in demanding environments.”

A Solution That Speaks to Our Strengths.

Midwest Scrap Management’s shredder operation is now on solid ground and continues ripping through an endless flow of metal. Painstaking evaluations, investigations and construction oversight resulted in a solution forged into an exact match for what the company needed from an engineering perspective within the context of business realities. Working closely with our project partners, we gave new life to another old industrial property inside Kansas City’s Blue River Valley Industrial Corridor, and our track record there grew a little longer.

New shredder operations site complete.

New shredder operations site complete.

“Many geotech firms have touched projects in the Corridor, but understanding all the brownfield surprises and old foundations that dot the subgrade has become second nature to our team at Alpha-Omega Geotech,” says Bush. “The steel mill history and the legacy of World War II industrial production makes this area unique, and we know it well.”

In fact, we know all of Kansas City pretty well. We can see its potential, even when others can’t, and we thrive on helping businesses give new purpose to old properties abandoned by passing eras. We realize our role isn’t glamorous, but we don’t work for attention. We work to empower our community by making the most of what the land has to offer. And the best reward is a vibrant hometown that’s not afraid to build its future on pieces of the past.

“Allowing land in the heart of the Kansas City area to go to waste just because it’s complicated and difficult to develop just isn’t acceptable in our view,” says Bennett. “That’s just not what we’re about. There’s opportunity just about everywhere if you’re willing to look hard enough and make it happen.”

Project Partner:

Structural Engineering: BSE